The merge is coming, and crypto may never be the same.

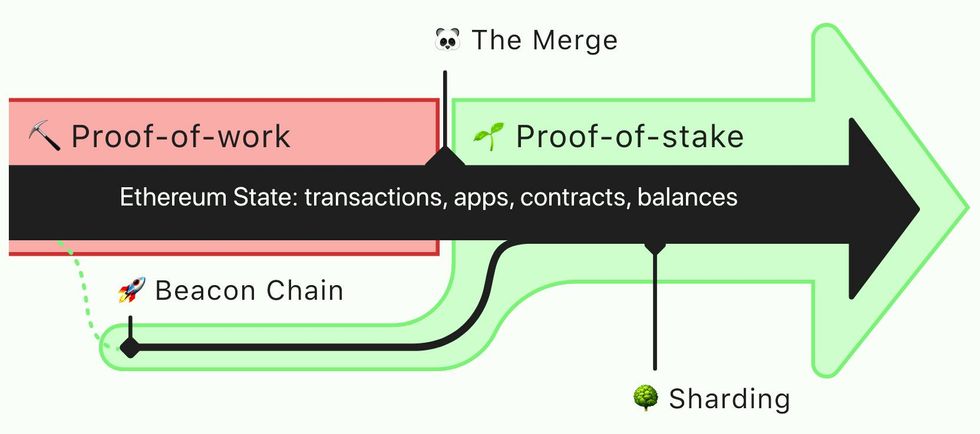

“The merge” is shorthand for Ethereum’s rapidly approaching switch from one compute-intensive form of blockchain verification to a much less resource-heavy method. In other words, the cryptocurrency will be switching from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake. This move, which is years in the making, changes how Ethereum maintains consensus—and drastically slashes power consumption.

“Ethereum’s power-hungry days will soon be numbered,” says Terence Tsao, Ethereum protocol developer at Prysmatic Labs. “And I hope that’s true for the rest of the industry, too.”

How proof-of-stake solves crypto’s climate crisis

Blockchains use a consensus mechanism to maintain integrity without a central authority. Ethereum, like most popular blockchains (including Bitcoin), currently relies on a consensus mechanism called proof-of-work. It places cryptocurrency miners in competition to solve a difficult algorithm.

The computational difficulty is in fact key to proof-of-work’s success. A single participant could defeat proof-of-work by owning a majority of all mining power (this is known as a “51 percent attack”), but the computational power required to achieve this makes a 51 percent attack against a large blockchain, such as Ethereum, very, very difficult.

Yet this strength is also a weakness, as computing power requires energy. Stories of mothballed coal plants converted to mining centers underscore the problem. Proof-of-work directly contributes to carbon emissions unless a mining center relies on clean energy—and that’s often not the case. A tracker maintained by the University of Cambridge estimates that Bitcoin alone consumes more energy per year than Finland, Belgium, or the Philippines.

Proof-of-stake takes a different approach. It asks validators to put up a large sum of a blockchain’s coin or token (the “stake”) for the right to serve as a validator. In the case of Ethereum, participates will have to stake 32 ETH (about $60,000 as of 12 August) to become validators. This is rewarded with additional Ethereum over time.

There’s no complex algorithm to solve. The tempo of new blocks is fixed, with validators randomly selected to add blocks to the chain. This drastically reduces energy consumption and, in doing so, slashes the carbon footprint.

“Ethereum will use at least 99 percent less energy post-merge, which is closer to solving a significant criticism, crypto’s environmental impact,” says Tsao. “When the long waited merge happens, we may see more green-conscious users on board.»

The merge clears its final hurdle

Changing a blockchain’s consensus mechanism isn’t easy, however. The threat of a “fork” looms. A fork occurs when some participants reject changes to the blockchain and take it in a different direction.

Ethereum’s most significant fork occurred when DAO, a decentralized venture capital fund, lost approximately US$150 million of ETH to a hacker whose identity remains disputed. The attack was eventually resolved by forking Ethereum. Ethereum Classic maintained the hack while conventional Ethereum returned the stolen ETH to its prior owners.

To mitigate the possibility of a fork, the Ethereum Foundation has conducted a series of trial runs to prove the merge can safely, securely occur without a technical issue. These trials switch blockchains used for Ethereum testing from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake. The most recent, and final, trial run involved the Goerli testnet blockchain on 10 August.

The tests weren’t flawless. Some validators went offline in each test for a variety of reasons. Ethereum can continue to function, however, so long as most validators continue to remain online and no group of validators falls out of consensus.

This infographic from Ethereum.org depicts the projected order of operations in the cryptocurrency’s pending «merge» to a proof-of-stake blockchain consensus mechanism. Ethererum.org

“A successful merge should be measured on the actual merge and the chain finalizing,” says Tsao. “Sure, the participation rate dropped, and peer count dropped, but the point is that the merge worked.” Developers will continue minor tests and make last-minute improvements in the coming weeks.

The Ethereum Foundation has even proposed the block where proof-of-work will end, and proof-of-stake begin: 58750000000000000000000. This block is expected to be mined sometime on 15 or 16 September.

Rumbles of resistance linger. Chandler Guo, an angel investor with roots in the Chinese cryptocurrency mining industry, has thrown his support behind the ETHW fork. An Ethereum fork that maintains proof-of-work is attractive to cryptocurrency miners which, in a proof-of-stake system, are no longer necessary.

Yet this effort doesn’t appear a serious threat. It’s unclear if other major players in the cryptocurrency industry will cooperate with an effort to fork Ethereum by listing it on exchanges or building out support in apps. This doesn’t mean a fork won’t occur—but a fork embraced by a tiny fraction of participants won’t delay or derail the merge.

With technical hurdles overcome, Ethereum looks set to make the switch, and its fate holds sway over crypto’s future carbon footprint. A failure would be a mark against proof-of-stake, but a successful merge will make Ethereum the largest proof-of-stake blockchain in the world and offer evidence that any blockchain can make the transition.

Source: IEEE Spectrum Computing