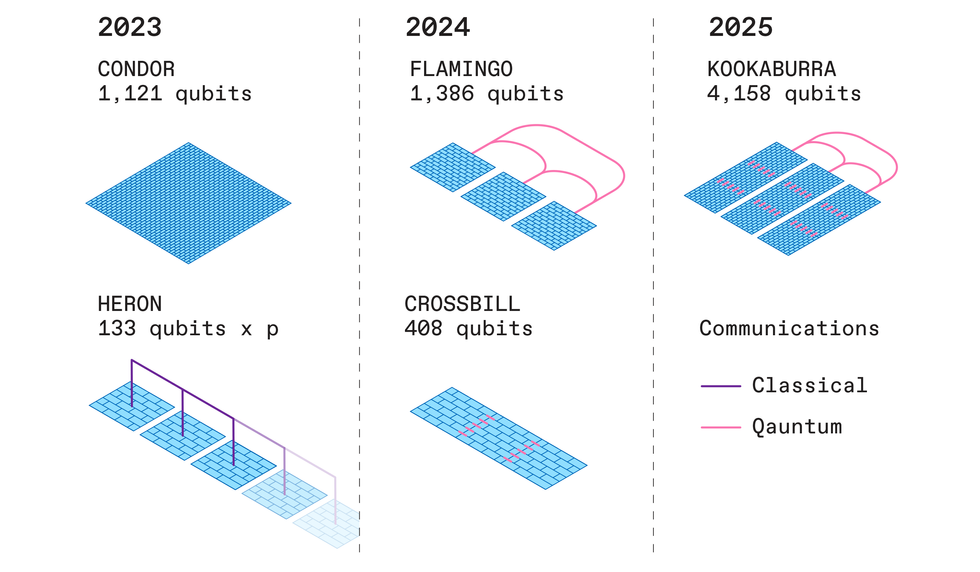

IBM’s Condor, the world’s first universal quantum computer with more than 1,000 qubits, is set to debut in 2023. The year is also expected to see IBM launch Heron, the first of a new flock of modular quantum processors that the company says may help it produce quantum computers with more than 4,000 qubits by 2025.

While quantum computers can, in theory, quickly find answers to problems that classical computers would take eons to solve, today’s quantum hardware is still short on qubits, limiting its usefulness. Entanglement and other quantum states necessary for quantum computation are infamously fragile, being susceptible to heat and other disturbances, which makes scaling up the number of qubits a huge technical challenge.

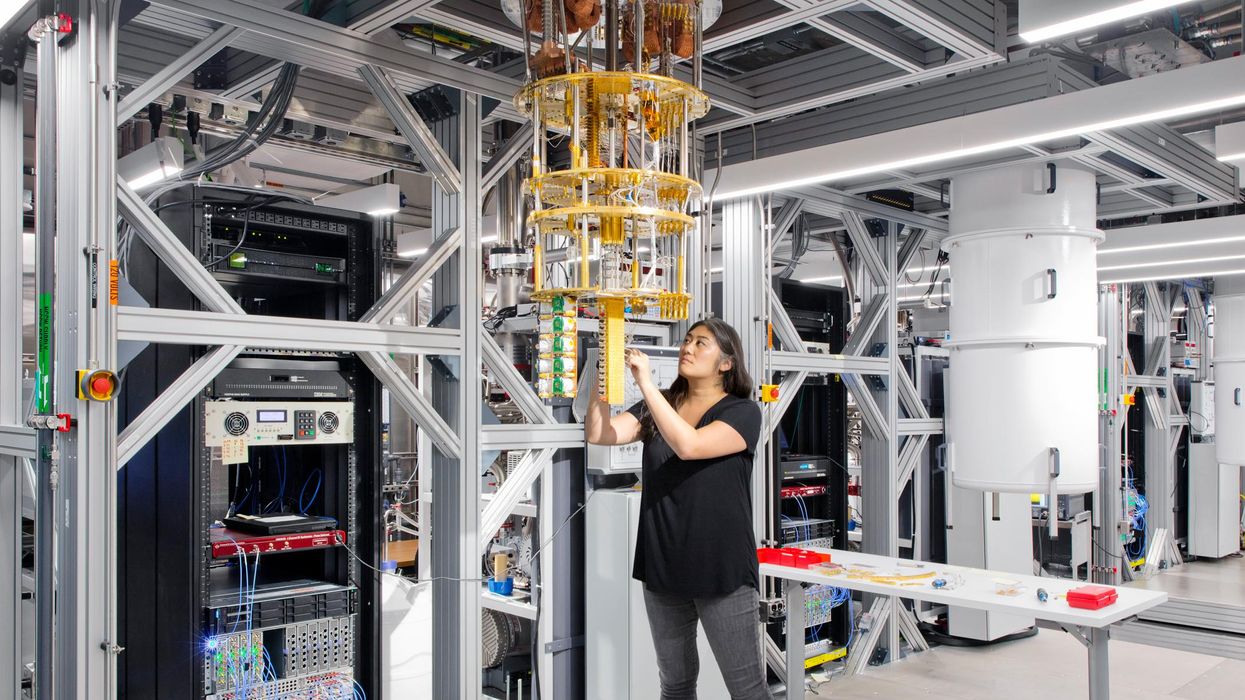

Nevertheless, IBM has steadily increased its qubit numbers. In 2016, it put the first quantum computer in the cloud anyone to experiment with—a device with 5 qubits, each a superconducting circuit cooled to near absolute zero. In 2019, the company created the 27-qubit Falcon; in 2020, the 65-qubit Hummingbird; in 2021, the 127-qubit Eagle, the first quantum processor with more than 100 qubits; and in 2022, the 433-qubit Osprey.

IBM expects to build quantum computers of increasing complexity over the next few years, starting with those that use the Condor processor or multiple Heron processors in parallel.Carl De Torres/IBM

Other quantum computers have more qubits than does IBM’s 1,121-qubit Condor processor—for instance, D-Wave Systems unveiled a 5,000-qubit system in 2020. But D-Wave’s computers are specialized machines for solving optimization problems, whereas Condor will be the world’s largest general-purpose quantum processor.

“A thousand qubits really pushes the envelope in terms of what we can really integrate,” says Jerry Chow, IBM’s director of quantum infrastructure. By separating the wires and other components needed for readout and control onto their own layers, a strategy that began with Eagle, the researchers say they can better protect qubits from disruption and incorporate larger numbers of them. “As we scale upwards, we’re learning design rules like ‘This can go over this; this can’t go over this; this space can be used for this task,’” Chow says.

Other quantum computers with more qubits exist, but Condor will be the world’s largest general-purpose quantum processor.

With only 133 qubits, Heron, the other quantum processor IBM plans for 2023, may seem modest compared with Condor. But IBM says its upgraded architecture and modular design herald a new strategy for developing powerful quantum computers. Whereas Condor uses a fixed-coupling architecture to connect its qubits, Heron will use a tunable-coupling architecture, which adds Josephson junctions between the superconducting loops that carry the qubits. This strategy reduces crosstalk between qubits, boosting processing speed and reducing errors. (Google is already using such an architecture with its 53-qubit Sycamore processor.)

In addition, Heron processors are designed for real-time classical communication with one another. The classical nature of these links means their qubits cannot entangle across Heron chips for the kind of boosts in computing power for which quantum processors are known. Still, these classical links enable “circuit knitting” techniques in which quantum computers can get assistance from classical computers.

For example, using a technique known as “entanglement forging,” IBM researchers found they could simulate quantum systems such as molecules using only half as many qubits as is typically needed. This approach divides a quantum system into two halves, models each half separately on a quantum computer, and then uses classical computing to calculate the entanglement between both halves and knit the models together.

IBM Quantum State of the Union 2022

While these classical links between processors are helpful, IBM intends eventually to replace them. In 2024, the company aims to launch Crossbill, a 408-qubit processor made from three microchips coupled together by short-range quantum communication links, and Flamingo, a 462-qubit module it plans on uniting by roughly 1-meter-long quantum communication links into a 1,386-qubit system. If these experiments in connectivity succeed, IBM aims to unveil its 1,386-qubit Kookaburra module in 2025, with short- and long-range quantum communication links combining three such modules into a 4,158-qubit system.

IBM’s methodical strategy of “aiming at step-by-step improvements is very reasonable, and it will likely lead to success over the long term,” says Franco Nori, chief scientist at the Theoretical Quantum Physics Laboratory at the Riken research institute in Japan.

IBM’s quantum leaps in software

In 2023, IBM also plans to improve its core software to help developers use quantum and classical computing in unison over the cloud. “We’re laying the groundwork for what a quantum-centric supercomputer looks like,” Chow says. “We don’t see quantum processors as fully integrated but as loosely aggregated.” This kind of framework will grant the flexibility needed to accommodate the constant upgrades that quantum hardware and software will likely experience, he explains.

In 2023, IBM plans to begin prototyping quantum software applications. By 2025, the company expects to introduce such applications in machine learning, optimization problems, the natural sciences, and beyond.

Researchers hope ultimately to use quantum error correction to compensate for the mistakes quantum processors are prone to make. These schemes spread quantum data across redundant qubits, requiring multiple physical qubits for each single useful logical qubit. Instead, IBM plans to incorporate error-mitigation schemes into its platform starting in 2024, to prevent these mistakes in the first place. But even if wrangling errors ends up demanding many more qubits, IBM should be in a good position with the likes of its 1,121-qubit Condor.

Source: IEEE Spectrum Computing