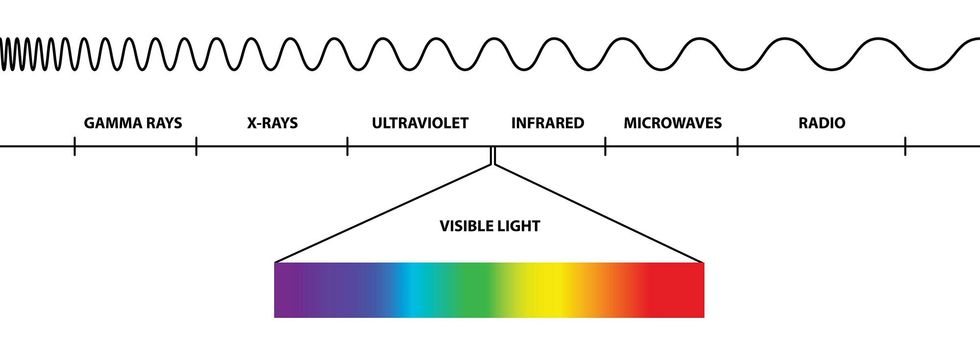

If you’re an astrophysicist trying to detect signals from the early universe after the big bang, Earth is not a great place to be. Yes, this planet is our home, warm and wet and brimming with life, but significant chunks of electromagnetic spectrum are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere, magnetic field and—more recently—the growing cacophony of wireless signals.

Astronomers could, in just the next few years, start to solve the problem in a remarkable way: Putting radio telescopes on the far side of the moon, where the moon’s mass would block out all that electronic noise. For radio signals, it is probably the quietest place in the inner solar system. That’s in part because the moon is tidally locked, meaning that the far side always faces away from Earth. It’s also because as the universe expands, many distant signals are shifted toward longer wavelengths that are impossible for earthly telescopes to detect.

The potential is tremendous. If telescopes on the moon can work in radio silence, scientists talk of detecting the magnetospheres of exoplanets circling other stars. Or gravitational waves, the invisible “ripples” in space-time caused by some of the most violent events in the distant universe. Or even far-infrared signatures of the so-called dark ages, the period of about 400 million years after the big bang before the first stars and galaxies began to form.

Much of the electromagnetic spectrum is invisible to Earth-based telescopes or drowned out by interference.LeonArt Studio/Alamy

But even this solution has a looming problem—namely, that everyone else interested in space has thought of the moon’s potential as well. Over the next two or three years, there could well be two dozen lunar missions, each one landing astronauts, starting mining operations—and transmitting on countless frequencies. There’s something of a lunar gold rush in progress, and astronomers want to make sure science doesn’t get trampled.

“We’ve talked about this sometimes as being a kind of Wild West mentality, a free-for-all, and we want to avoid that,” says Jack Burns of the University of Colorado in Boulder. He and many colleagues are sounding the alarm, at conferences and in peer-reviewed journals, hoping to ensure radio silence for the moon’s far side before it’s too late.

Burns has been an investigator on some of the earliest efforts in moon-based radio astronomy, including Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus spacecraft, which in February made the first-ever landing by a commercial company on the lunar surface. One of its payloads was an antenna array called ROLSES, meant partly to test for charged particles near the lunar surface. Odysseus had a hard landing, but it was one step on a roadmap of experiments physicists have planned. An experiment called LuSEE-Night could be launched as soon as 2026, carried to the back of the moon by a lander from Firefly Aerospace.

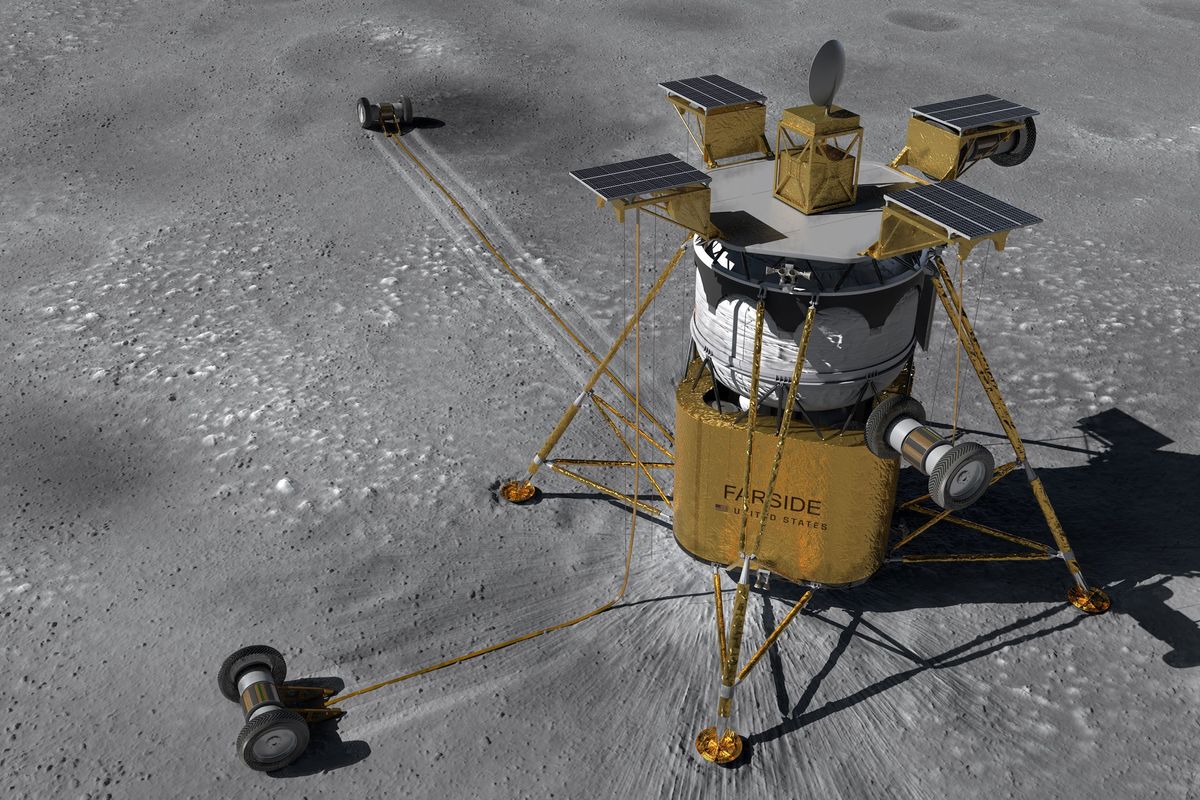

A bigger project, called FARSIDE, aims to lay out a 10-kilometer interferometer in an area blocked from Earth. If it works, it will listen for signals from the most distant corners of the universe—signals that could easily be drowned out by lunar satellites sent from the United States, China, India or, for that matter, Elon Musk’s SpaceX or other private companies.

“We’re looking for this incredibly weak signal,” says Joseph Silk, an astrophysicist who has done pioneering work on understanding the early universe. “We’re looking way back to the early universe.”

Burns is quick to say that the lunar gold rush can actually be a good thing for scientists. “This is a whole new era of space and space exploration, these public-private partnerships, these entrepreneurs, these billionaires who are investing in space,” he says. They may be out to mine the moon or profit from government programs, but they’re also building infrastructure—landers, communications networks and so forth—that scientists can use as well as entrepreneurs.

The worry is that things will happen that nobody anticipated. For instance, electrical circuits on spacecraft tend to “leak” unintended signals into space unless they’re adequately shielded. Imagine a satellite in lunar orbit, perhaps sent to observe the near side of the moon, ruining the observations by a radio telescope on the far side when it passes over.

The LuSEE-Night experiment, shown here mounted atop Blue Ghost Mission 2 in an artist’s concept, is planned for a mission to the far side of the moon.Firefly Aerospace

Richard Green of the Steward Observatory at the University of Arizona tells of a conference he attended in Paris last month, where he talked about interference risks with people from major European aerospace companies. “Their reaction was, by and large, ‘That’s really interesting. We were unaware,’” he says.

Green says he doesn’t run into resistance, but it’s different than dealing with government agencies like NASA. “There’s a new pressure, which is to minimize expense as well as optimizing performance. So if a commercial operator doesn’t need to spend on the extra design complication of careful shielding, they won’t do that voluntarily.”

So how to solve the problem before it becomes a crisis? Many scientists suggest working out a treaty through the International Telecommunication Union, an agency of the United Nations. Past agreements—the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, the Antarctic treaty—have been effective, though none is a perfect model for protecting scientific sites on the lunar far side.

Green says he came away concerned after previous experience at the United Nations. “They work by unanimous consent. So every single nation has to agree. That is to say Russia, China, the U.S. and Iran. And right now, Russia and Iran are in a mood to obstruct. So there are reasons why progress could, possibly, be slow.”

“But we have to do it,” says Silk. “Otherwise, it will be chaos on the moon.”

Source: IEEE Spectrum Telecom Channel